Program Notes for February 10 & 11, 2023

Barber & Brahms

Margaret Brouwer

Remembrances

Composer: born February 8, 1940, in Ann Arbor, Michigan

Composed: 1996

written for the Roanoke Symphony, dedicated to Robert Stewart

Premiere: Roanoke Symphony, Yong-Yan Hu, guest conductor, Roanoke, VA, March 18, 1996

Duration: 14 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 (2nd picc.) 2 EH 2 2(2nd cbsn.); 4331; timp., 2 perc., hp., strings

This tone poem is an elegy and a tribute to Robert Stewart who was a musician, composer, sailor and loved one. Beginning with an expression of grief and sorrow, the music evolves into a musical portrait, full of warm memories, love and admiration, and images of sailing. Typical of elegies and tone poems, such as "Death and Transfiguration" by Strauss, it ends in a spirit of consolation and hope.

REVIEWS

"...Next was RSO Composer- in-Residence Margaret Brouwer's lovely tone poem "Remembrances." This was Brouwer at her best: lyrical, accessible, powerful and deeply moving. I have heard a number of Brouwer's works in several venues, and "Remembrances" made the best impression by a long shot. If more contemporary composers would write like Brouwer in this vein, the uneasy armed truce between audiences and modern music would quickly come to an end....In the long second section there were numerous gorgeous solos for winds, including a ravishing line from solo oboe over timpani roll and pedal tones from the double basses. There was also a lovely soliloquy for clarinet. The mood alternated between gentle sorrow and striving affirmation. "Remembrances" ended on a rising three-note figure and the piece was quickly awarded enthusiastic applause, bravos and a standing ovation." - Seth Williamson, Roanoke Times, March 19, 1996

"The moving "Remembrances" is 'an elegy and a tribute' to a deceased loved one. Its 15-minute span allows it to move with unhurried sincerity from mourning to hard-won reassurance. With its consonant tonality, it is the most stereotypical "American" piece on this disc." - Raymond S Tuttle, International Record Review, June 2006

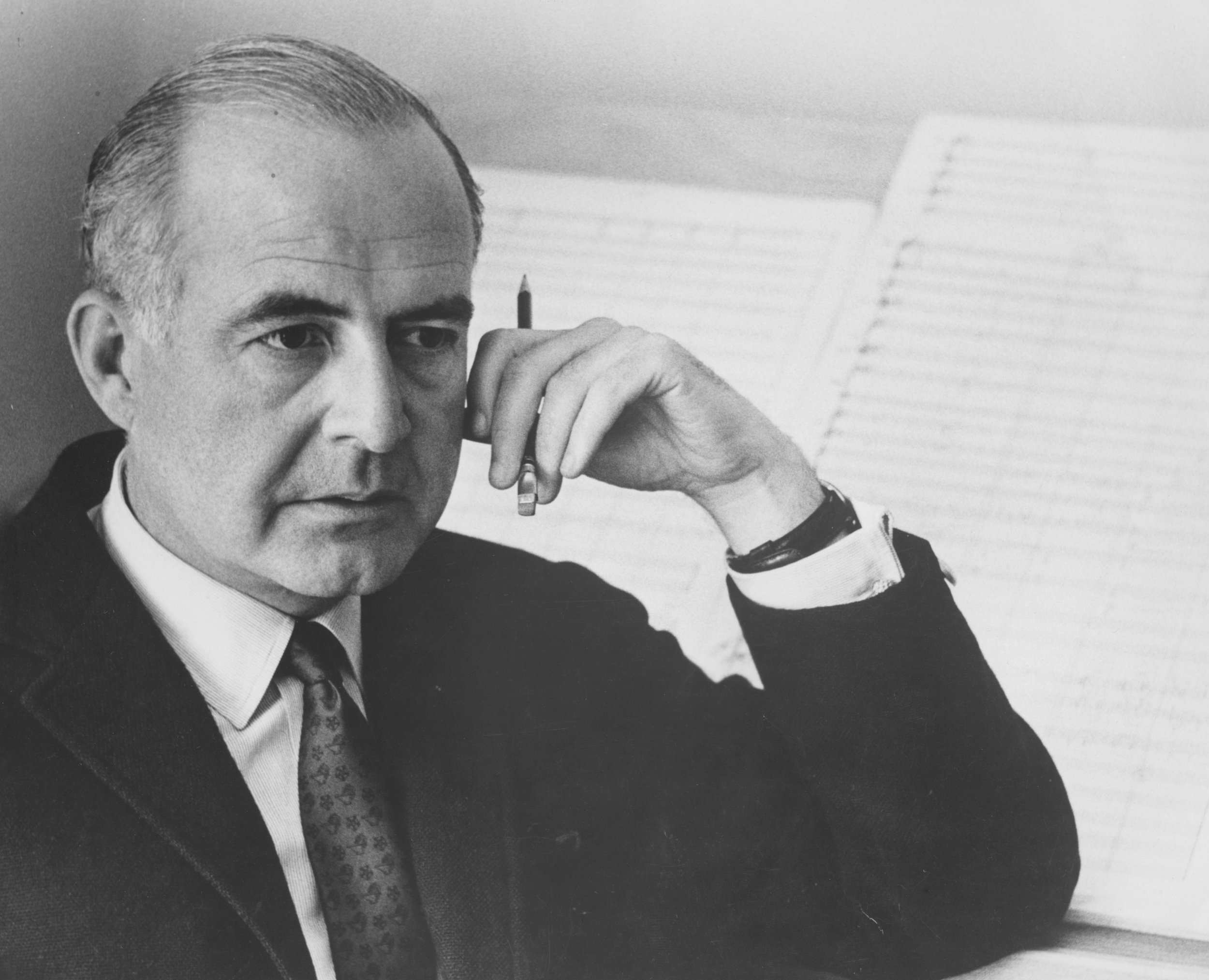

Samuel Barber

Violin Concerto, op. 14

Composer: born March 9, 1910, West Chester, PA; died January 23, 1981, New York City

Work composed: 1939, rev. 1948

World premiere: Eugene Ormandy led the Philadelphia Orchestra, with violinist Albert Spalding, on February 7, 1941. The revised version was first performed by violinist Ruth Posselt, with Serge Koussevitzky leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on January 6, 1949.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, snare drum, piano, and strings

Estimated duration: 25 minutes

Samuel Barber wrote the Violin Concerto, his first major commission, for Samuel Fels, the inventor of Fels Naptha soap, on behalf Fels’ adopted son, violinist Iso Briselli. Barber began work on the concerto in Switzerland in the summer of 1939, but, due to what he described in a letter as “increasing war anxiety,” Barber left Europe in August and returned home with the final movement still unfinished.

At the end of summer 1939, Barber sent the first two movements to Briselli for comment. Briselli was unimpressed, describing them as “too simple and not brilliant enough for a concerto.” Taking these comments to heart, Barber resolved to write a final movement that would afford “ample opportunity to display the artist’s technical powers.” Briselli found fault with this movement as well, calling it “too lightweight” in comparison with the other movements. In a letter to Fels, Barber wrote, “[I am] sorry not to have given Iso what he had hoped for, but I could not destroy a movement in which I have complete confidence, out of artistic sincerity to myself. So we decided to abandon the project, with no hard feelings on either side.” Barber later approached violinist Albert Spalding, who immediately agreed to premiere the work. Because of all the controversy generated by the third movement, Barber gave the concerto a humorous nickname, the “concerto del sapone,” or a “soap concerto,” a reference both to Fels Naptha and the melodrama of soap operas.

Reviews praised the concerto as “an exceptional popular success” and Barber for writing a concerto “refreshingly free from arbitrary tricks and musical mannerisms … straightforwardness and sincerity are among its most engaging qualities.” The late annotator Michael Steinberg called the opening of the first movement “magical,” and goes on to ask, “Does any other violin concerto begin with such immediacy and with so sweet and elegant a melody?” Few works, certainly few concertos, draw the listener in so quickly, and keep our attention focused so completely. The Andante semplice features a heartbreakingly beautiful oboe solo – classic Barber in its yearning – and the violinist answers it with an impassioned yet surprisingly intimate melody that suggests the violin musing aloud to itself.

The finale, a rondo theme and variations, is particularly impressive. In his program notes for the 1941 premiere, Barber wrote, with characteristic understatement, “The last movement, a perpetual motion, exploits the more brilliant and virtuoso characteristics of the violin.” But as biographer Barbara Heyman points out, “This is one of the few virtually nonstop concerto movements in the violin literature (the solo instrument plays for 110 measures without interruption).”

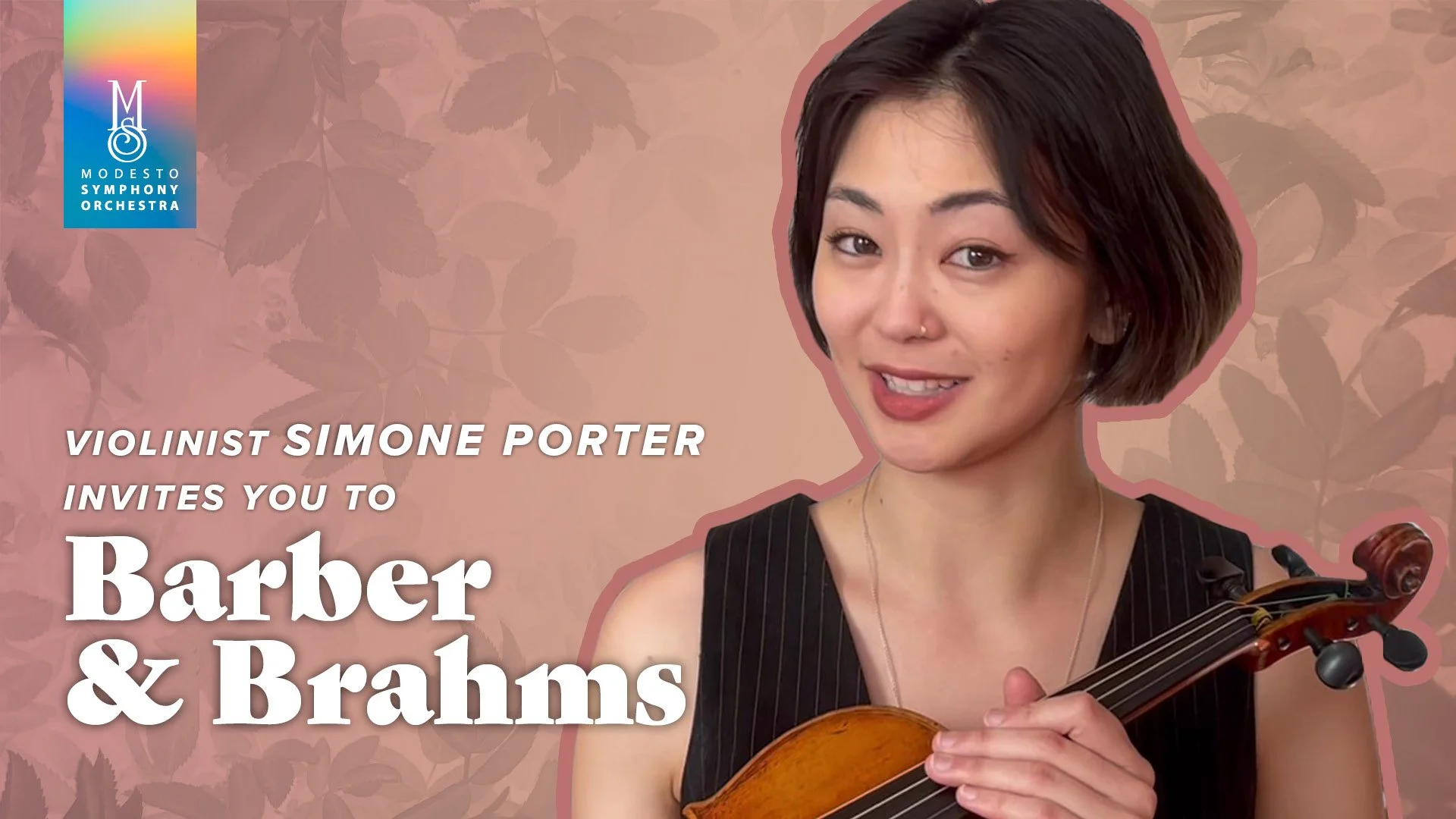

Watch to learn more about Barber’s Violin Concert from violinist Simone Porter!

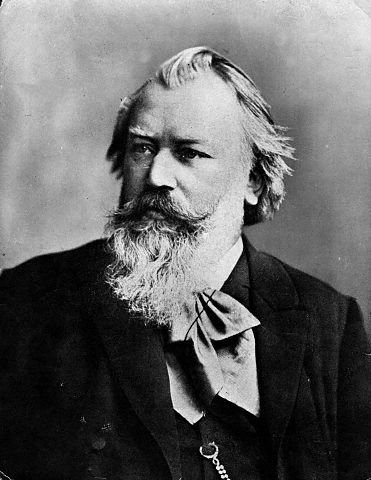

JOhannes Brahms

Symphony No. 2 in D major, op. 73

Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Work composed: During the summer and fall of 1877

World premiere: Hans Richter led the Vienna Philharmonic on December 30, 1877

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration:39 minutes

Less than a year after the successful premiere of Johannes Brahms’ first symphony, on November 4, 1876, the composer left Vienna to spend the summer at the lakeside town of Pörtschach on Lake Wörth, in southern Austria. There, in the beauty and quiet of the countryside, Brahms completed his second symphony. Pörtschach was to be a productive place for Brahms; over the course of three summers there he wrote several important works, including his Violin Concerto. In a letter to critic Eduard Hanslick, a lifelong Brahms supporter, Brahms wrote, “The melodies fly so thick here that you have to be careful not to step on one.”

Unlike Brahms’ first symphony, which took more than 20 years to complete, work on the second went smoothly, and Brahms finished it in just four months. Brahms felt so good about his progress that he joked with his publisher, “The new symphony is so melancholy that you won’t stand it. I have never written anything so sad … the score must appear with a black border.” In a different letter, Brahms self-mockingly observed, “Whether I have a pretty symphony I don’t know; I must ask clever people sometime.”

As Brahms composed, he shared his work-in-progress with lifelong friend Clara Schumann. “Johannes came this evening and played me the first movement of his Second Symphony in D major, which greatly delighted me,” Schumann noted in her diary in October 1877. “I find it in invention more significant than the first movement of the First Symphony … I also heard a part of the last movement and am quite overjoyed with it. With this symphony he will have a more telling success with the public as well than he did with the First, much as musicians are captivated by the latter through its inspiration and wonderful working-out.”

The Symphony No. 2 is often described as the cheerful alter ego to the solemn melancholy of the Symphony No. 1. Brahms uses the lilting notes of the Allegro non troppo as a common link throughout all four movements, where they are repeated, reversed and otherwise, in Schumann’s words, “wonderfully worked-out.” In the extended coda, Brahms introduces the trombones and tuba, casting a tiny shadow over the sunny mood. The Adagio’s lyrical cello melody hints at the wistful melancholy that characterizes so much of Brahms’ music. The Allegretto grazioso is remarkably gentle, and the infectious joy of the closing Allegro con spirito expands on the first movement’s amiable mood, so much so that at the Vienna premiere, the audience demanded an encore.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com