Program Notes for MAy 10 & 11, 2024

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

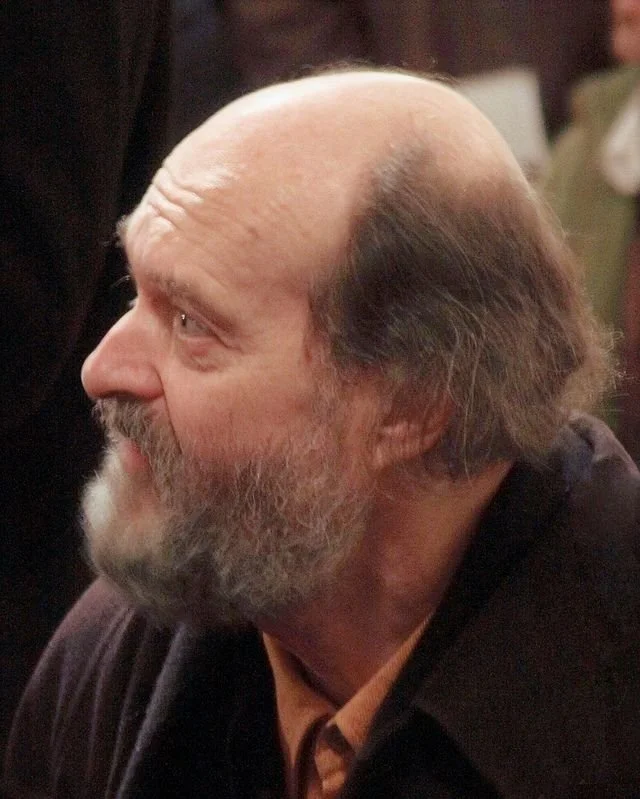

Arvo pärt

Fratres

Composer: born September 11, 1935, Paide, Estonia

Work composed: 1977

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

The crystalline quality of Arvo Pärt’s music evokes the wintry climate of his native Estonia. Pärt achieves this shimmering transparency through single notes, a compositional style he named “tintinnabulation,” Latin for “little bells.” Pärt explains, “I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played. This one note, or a silent beat, or a moment of silence, comforts me. I work with very few elements – with one voice, two voices. I build with primitive materials – with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells, and that is why I call it tintinnabulation.”

At the time Pärt composed Fratres, he was also immersing himself in the sound world of medieval and Renaissance music. Music from these periods did not often indicate which instruments or voice parts should be used, a practice Pärt employed with Fratres. This choice showcases notes and melodic phrases, rather than particular timbres, or sound colors.

Fratres features a series of variations on a simple stepwise theme, which reappears in several different octaves. Underneath the gently shimmering variations, the low strings maintain a steady drone. The overall effect is meditative, enveloping the listener in a mood of reflection.

AMy BEach

Peace I Leave With You

Composer: born September 5, 1867, Henniker, NH; died December 27, 1944, New York City

Work composed: 1891

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: a cappella SATB chorus

Estimated duration: 1.5 minutes

Amy Beach’s musical accomplishments include several firsts: the first American woman to compose and publish a symphony – and the first American woman to have a symphony performed. She is also one of the first American composers – of any gender – whose musical training occurred wholly within the United States, rather than Europe. As such, Beach’s approach to composition and her aesthetics are uniquely American, and she did not measure the quality of her work by comparing it to music by European composers, unlike some of her contemporaries.

Beach’s prodigal musicality emerged as early as age two, as documented by her mother Clara: “Her gift for composition showed itself in babyhood before two years of age. She could, when being rocked to sleep in my arms, improvise a perfectly correct alto to any soprano air I might sing … She played the piano at four years, memorizing everything that she heard correctly ...” Clara was Beach’s first piano teacher; the young girl later studied piano in Boston. By the time she reached age 12, Beach’s parents were being lobbied by musical impresarios eager to launch their wunderkind daughter onto the concert stage. Beach’s parents declined, allowing Beach to refine her piano skills and pursue other musical studies through her teenage years. She made her concert debut at age 16, to great acclaim, and continued concertizing for the next two years, until her marriage to Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, 25 years her senior.

In 1930, Beach moved to New York, where she formed a close relationship with St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, and wrote many liturgical choral works for their choir. It is likely her 1891 anthem, “Peace I Leave with You,” with text from the Gospel of John, was first sung there. The simple elegance of Beach’s homophonic setting emphasizes the clarity and meaning of the words to create a gentle benediction.

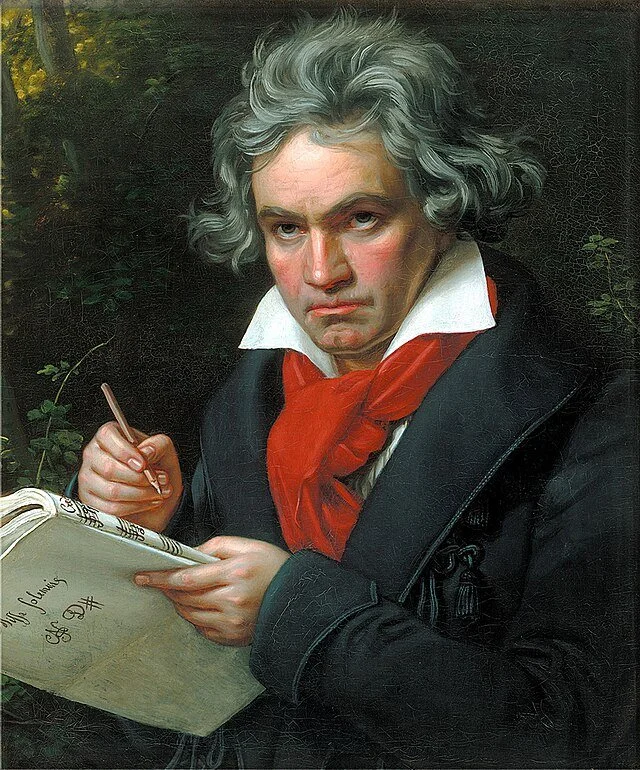

ludwig van beethoven

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral”

Composer: born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

Work composed: Beethoven made preliminary sketches in 1817-18, but most of the music was composed between 1822–24. Beethoven finished his Ninth Symphony in February 1824, and dedicated it to King Frederick William III of Prussia.

World premiere: Beethoven conducted the first performance on May 7, 1824, at the Kärntnerthor Theater in Vienna.

Instrumentation: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists, four-part mixed chorus, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, cymbals triangle and strings.

Estimated duration: 70 minutes

The Ninth Symphony extends beyond the realm of the concert hall and has permeated Western culture on many levels, including socio-political and commercial arenas. The music of the Ninth, particularly the “Ode to Joy” melody of the final movement, is so familiar to us that it has lost its unique character and taken on the quality of folk music; that is, it has shed its “composed” identity as a melody written by Ludwig van Beethoven and simply exists within the communal ear of our collective consciousness.

While some classical works are inextricably linked to the time in which they were written, Beethoven’s profound musical statements about freedom, equality, and humanity resonate just as powerfully today as they did at the Ninth’s premiere. This was evident to the entire world 35 years ago, when Leonard Bernstein conducted an international assembly of instrumentalists and singers in a historic performance of Beethoven’s Ninth at East Berlin’s Schauspielhaus (now Konzerthaus) on December 22, 1989, three days after the fall of the Berlin Wall. To emphasize the historic event, Bernstein substituted the word “freedom” for “joy” in the famous lyrics by the poet Friedrich Schiller in the final movement. The performance was broadcast on television worldwide, attracting more than 200 million viewers.

By 1822, Beethoven was completely deaf and emotionally isolated. Five years earlier, at the age of 47, he had written in his journal, “Before my departure for the Elysian fields I must leave behind me what the Eternal Spirit has infused into my soul and bids me complete.” Alone and embittered, Beethoven focused almost exclusively on his musical legacy.

The lofty salute to the human spirit expressed in Schiller’s poem An die Freude (To Joy) had resonated with Beethoven for many years; in 1790 he set a few lines in a cantata written to commemorate the death of Emperor Leopold II; he also included portions of Schiller’s poem in his opera Fidelio. “The search for a way to express joy,” as Beethoven described it, was the subject of his final symphony. To that end, Beethoven edited and arranged Schiller’s lines to suit his musical and dramatic needs, using a melody from the Choral Fantasy he had written 20 years earlier.

The symphony opens with the strings sounding a series of hollow open chords, neither major nor minor, which are harmonically ambiguous – what key is this? The fifths build into a massive statement featuring a weighty dotted rhythmic theme. The intensity of this movement foreshadows the finale.

As was his wont, Beethoven broke with symphonic convention by writing a second-movement scherzo. The music bursts forth with dramatic string octaves and pounding timpani. The main theme, a contrapuntal fugue, gives way to a demure wind melody. Underneath its playful simplicity, the barely contained agitation of the scherzo pulses in the strings, like a racehorse pawing at the starting gate.

In a symphony synonymous with innovation, Beethoven’s most significant departure from convention is the inclusion, for the first time, of a chorus and vocal soloists in a formerly exclusively instrumental genre. The cellos and basses play an instrumental recitative, later sung by the baritone, which is followed by the unaccompanied “Joy” melody. Beethoven then presents several instrumental variations, including a triumphal brass fanfare. The baritone soloist introduces Schiller’s poem with words of Beethoven’s: “O friends, not these tones; instead, let us strike up more pleasing and joyful ones.” The chorus repeats the last four lines of each stanza as a refrain, followed by the vocal quartet. A famous interlude, the Turkish March, follows (this music was considered “Turkish” because of the inclusion of the triangle, cymbals and bass drum, exotic additions to the orchestra of Beethoven’s time). After a number of variations, the chorus returns with a monumental concluding double fugue.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com